INSIGHTS: Vincent van Haaff,

acoustician, studio designer and president of Waterland Group

Interviewed by Mel Lambert in February, 1998  Vincent Van Haaff, president of LA-based Waterland Group, is a renaissance man who puts the quality of his designs above all other criteria. As he readily confesses, his studio designs are based on equal amounts of aesthetics and acoustical science, with a focus on the specific tastes and personality of the facility's owners. For van Haaff, a recording studio or post facility is more than just a space in which we record or mix a project. "It is," he concedes, "a carefully crafted environment in which we witness the creation of sonic art." Vincent Van Haaff, president of LA-based Waterland Group, is a renaissance man who puts the quality of his designs above all other criteria. As he readily confesses, his studio designs are based on equal amounts of aesthetics and acoustical science, with a focus on the specific tastes and personality of the facility's owners. For van Haaff, a recording studio or post facility is more than just a space in which we record or mix a project. "It is," he concedes, "a carefully crafted environment in which we witness the creation of sonic art."

Since starting his career in his native Holland, first as an architectural student and then as a film student, Van Haaff soon discovered his true destiny: designing studios for a variety of clients. Since his auspicious beginning in 1976 at Kendun Recorders/Sierra Audio in Los Angeles, Van Haaff has been involved with a cornucopia of studios around the world, including Conway Recording, Los Angeles (many original designs and upgrades since the early Seventies, as well as a new studio complex); A&M Studios, LA (several remodeling projects, plus design of the new Studio "C" for DVD and surround sound mixing); Sony Music Studios, NYC (control room and studio. plus mix room); Project 50, Bedford, NY (residential studio); Philips Interactive Media, Los Angeles (recording and digital mastering suites); Capitol Records, Los Angeles (Studio "C" Mix room); Herb Alpert Foundation, Santa Monica, CA (recording studio and artist's studio); Richard Landis/Loud Music, Nashville (studio and mix room); writing studios for West Side Sound/ David Schwartz, Aaron Zigman and Eli Gabrieli; Burnish Stone Studio, Tokyo (studio and control room, plus two studios as expansion on existing facility); The Castle Studios, Nashville (studio and residence); Woodstock Studio/A I M Corp., Karuizawa, Japan (resort recording and A/V studio); Ocean Entertainment, Burbank (studio and offices); 525 Post Production, Hollywood (post room for video/film); Samuel J. Scott Productions, Las Vegas (post and sweetening studios); Post-Logic, Hollywood (audio-video post and recording); Music Grinder Studio, Hollywood (Studio "A" and offices); Trebas Institute of Recording Arts, Hollywood (studio, control room, offices and teaching-spaces); Soundcastle Recording, Los Angeles (studio and control room); The Complex, West LA (studios and control rooms); Madhatter Studios, LA (studio and control room); Manta Sound Studio, Toronto (studio and control room); Post Logic, Hollywood (audio-video layback, post and Foley); Ground Control, Santa Monica (two studios and a control room); Skip Saylor Recording, LA (mix room); The Village Recorder, West LA (studios, Control Room "A" and "B"); Rubber Dubbers, Glendale (Foley Stage and control room); Monterey Sound, LA (control room and studio); Rusk Sound, LA (control room and studio); plus many more. Current assignments include Lobo Recording, New York; project studios for Glenn Frey, Don Henley and Michel Colombier; Bouquet Digital Studios, Port Hueneme, CA; and 99 Attorney Street Studios, New York.

Tell us a little more about your background.

I studied architecture and theater design in Europe. Luckily my brother - Fransois is 15 years older than me - was an electronics engineer, and was always futzing around as a ham-radio operator. As a [young boy] it was of course very intriguing to watch someone messing about with antennas on the roof; to help Fransois wire. In high school I got into design of loudspeakers for my buddies in bands - it was trial and error, and again listening to advice from my brother. But, by the time I got out of architecture school, the prospect of sitting behind a drafting desk in Holland for the next 15 years, working underneath some famous architect, wasn't really appetizing. So, I went to film school in London for half a year to see if there were any other avenues for me - and, yes, I was intrigued with making movies. Nothing to do with architecture; just something adventurous and completely different. I was usually walking around with a 16 mm camera on my shoulder. Summertime in London can be a very sticky; it was a bear to carry around this heavy equipment. There was a guy with a microphone boom and a Nagra around his shoulders. At one point I turned and said: "You have the greatest job because at least you can put your stuff down while we're shooting!" So I went from camera to sound again. I then met a filmmaker in Amsterdam who told me that he had a friend working with Stevie Wonder in New York at Electric Ladyland [during the 1974 recording of "Fulfillingness"]. "Why don't you just go visit him, and see if you can get a job." he suggested. And that's what I did. I then met Malcolm Cecil [with Robert Margouleff, partners in Tonto's Expanding Headband, and developers of a sophisticated early synthesizer], who said I should go visit Roy Cicala at Record Plant, where I got a job soldering and sweeping the floor - I was basically assisting and making copies. Then The Troupe sort of split off from Stevie Wonder, and went back to Los Angeles with them. I had various jobs here; lived in a macrobiotic commune . . . remodeled a guest house in back of a villa in Beverly Hills as a carpenter. One day Bob [Margouleff] called and said there is a job available at Kendun Recorders. So the next day I went over to visit [owner] Kent Duncan, who hired me. He put me together with Carl [Yanchar, now president of Wave:Space]; I ended up that same morning sitting in the shed next door to the studio, wiring connectors.

What else were you doing at Kendun? A bit of everything?

Yes. I got to assist once in a while. Eventually Kent found out that I had an architecture background. He had started Sierra Audio with [acoustician/designer] Tom Hidley, and I was given the green light to set up a drafting table. Soon, I was helping to design recording studios. The first assignment was Pace-Arrow Studios [in Evanson, near Chicago], then Rusk Sound Studios here [in Los Angeles]. The two owners, Sam Kaufman and Randy Urlich, had heard through the grapevine that I'd declared myself independent from Sierra Audio and came around to my house. "We're building a studio on La Brea," they said "Can you help us?" Rusk was formerly a Liberty Records [an existing, albeit outdated studio]. We cleared the old studio upstairs and it was basically my first hands-on job.

That was the era of Donna Summers [working at Rusk] with [producer] Giorgio Moroder, and a bunch of other sessions. It was a really nice room, and very well isolated; we had traffic on La Brea Avenue going by day and night. Somewhere near the end of that project, Buddy Brundo from Conway Recording came around to say that he had just bought his partners out, and wanted to remodel the studio. The site was a little slice of land with a building that was the front office and a small studio. We expanded it out and the rest, as they say, is history.

Last year marked Conway's 20th Anniversary. You've been involved with Buddy and his crew for that long?

Yes, throughout every step of the way! The same with A&M Studios; it's not a hit and run operation. I'm very proud of having worked continuously with Herb Alpert and the family there since we first met some 12 years ago. I remodeled Studio "A" in 1986, and have worked on most of the other tracking and mixing rooms - Studios "B," "D" and "M" - as well as the new DVD-ready, 5.1-channel Studio "C," which we completed in the Fall of last year. [Herb Alpert and his partner Jerry Moss - the "A" and "M" of the record label's name - sold the complex to Polygram in 1992.] I've also built a general-purpose studio, and Artist's Studio for the Herb Alpert Foundation, based in Santa Monica.

| Henson Studios "A" formerly A&M, built 1985

Photo: Vincent van Haaff |

Looking back at the designs you completed in the late Seventies and through the Eighties, I'm struck by the fact that you were working with most of the leading facilities in Hollywood and Los Angeles.

Yes, I was very lucky to fill the void left by Tom Hidley, who had been major West and East Coast designer until then. But Tom was working a lot in Europe - living in Switzerland at then Maui - and designing mainly overseas. I was the local guy that was incredibly lucky to get the clientele who saw eye to eye with me. And oftentimes they were in my own age group - from the rock and roll artist who wanted to have a studio built in his garage to the full-on facility. For [project-studio owners], I was useful as a reality check: By saying "You could do this or that, but don't waste your money on that [treatment], for example." I'm a cheap Dutch man! [Laughs.] I really like to build studios out of readily available materials. Rather than going out and buying fancy "acoustic" materials, which at the hardware store costs a tenth of the price. I like to give feel good value for money.

| How do you secure new business?

Primarily dealing with existing clients, and word of mouth Generally, people who are interested in setting up something very personal; an expression of personal tastes as well as a means of bringing about more expression in their lives. A recording studio is not only an expression of the personal taste for an artist, it is also a way of putting a foundation for their future creativity. That space has to be comfortable and inspiring, and a catalyst. I take that concept and certainly will stop them from going overboard, or off in the wrong direction. I've been incredibly lucky to work with people who really got into this space and the process. Herb Alpert is a perfect example. As a musician and a studio Alumnus he was involved in turning that [former film and TV shooting stage] into somewhere he was happy to record in. It was as if he was galloping creatively ahead, and I was just holding on for dear life! Making sure that all the technical and necessary parts would fit, as well as lighting, air conditioning and so on. A great recording studio is a joy for mankind. In the middle ages, people build cathedrals; in this day and age we build beautiful studios. They can have a similar kind of effect, because the product - whether it's a sermon or a piece of music in a Lutheran church - is meant to be memorable. People who listen to a CD by someone that was inspired to bring about this greatest work, can be inspired themselves.

Following that analogy with cathedrals, what studio is your "Notre Dame" or "St. Patrick's?"

The one that I enjoyed most is Conway Recording. All the rooms have a similar. non-pretentious "soul." There is something very good going on, and you can feel it.

| Conway Recording Mixroom "B" backwall built 1983

Photo WL |

So you meet with your client for the first time. They say: "Here's $1 million dollars; build me a studio." How do you find out what it is they're about?

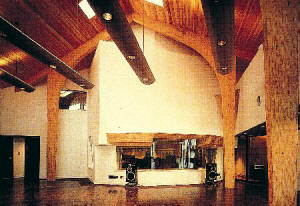

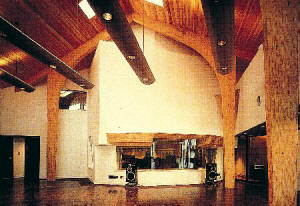

I go visit them at home. We have lunch, or we have dinner. I'm blessed with a certain a gift of being able to judge a person pretty well; to see what their inspirations are. We talk about art or music. Of course, we become friends; I need to know that person to become a friend. A good example of that process is a project I did in Japan from the ground up. Woodstock Studio is a resort studio in Karuizawa, high in the mountains near where the recent Winter Olympic Games were held. The buildings include overnight lodgings for 20 people, a kitchen, dining, recreation rooms and offices for the production staff. I finished the project in 1992. An engineer in Japan had been working both A&M and Conway, and had told somebody in Tokyo that if they wanted to build a studio then they should go visit Vincent. After we had hung out for a couple of days, the first thing I said to him, was: "You have a piece of land that you want to build on. And you want to build the most beautiful studio in Japan and attract all these great artists. Let me come to Japan for four or five days. I want to see the land. I want to smell the flowers. I want to trudge around in the mud, and feel what it's about there. [Woodstock was built on the site of former farmland, near one of the Japan's most famous summer and winter vacation resorts some 95 miles from Tokyo.] I had not only get to know the person and his dreams, but to personalize that dream. That is one of the most essential parts of the process - I would want to work in that studio. If it is the best studio in Japan, then it's the best studio for me to work in Japan; I design it for myself, in a sense.

Suppose it is an existing plan? Is that more of a restriction for you?

Yes, very much. And if I don't get to see the place that people ask me to work on, I'll let them know that I prefer to consult. I'll maybe do it by fax. I'm not going to sit down and do an elaborate set of blueprints. I'm not going to try to visualize as much. Visualization of the finished product is an important aspect of the quality control I have to maintain throughout the project.

Do you visualize walking through the complex?

Absolutely. And when the drawings are generated from the plotters, I can really see whether it is the overlay of what I saw. If there is anything askew in that drawing, I immediately catch it. It's an odd thing.

I often wonder if designers spend too much time on the aesthetics of color schemes, when you realize that the basic shape is lacking in intimacy, for example.

If you ask a string player what it feels like to actually listen to a violin in that space, they will say: "Geez, it looked really interesting, but I couldn't read my sheet music because the lighting was shining on the walls, and not on my score." The designer missed the point - what is the actual usefulness of the space?

Session players are probably the most critical of all because they do this day after day. Some studios become their favorites because not only is the coffee hot, but they can actually work there. In general, they've a 9:30 downbeat and two and a half hours is heavy concentration. They see the music for the first time when it comes out of the arranger's briefcase. I like to use natural materials, and not get to fancy in the colors. And not get too crazy in the shape of things. It is easier to walk past a table with rounded corners than with corners that have spikes in your direction, right? It's just a natural form; natural shapes of things are incredibly important. At the same time, you don't want to be everything to everybody. There has to be a sense of personality about the space that speaks for itself but which can be easily adapted to.

You've been hired to remodel the second floor at The Village Recorders, West LA, and add two scoring stages. How did that commission come about?

I have worked on most of the rooms at The Village, including "A," "B" and "D, which are relatively big areas. We are now investigating with the structural engineers ways of re-supporting the second floor - where there are two large-volume auditoriums [in the former Masonic Temple] - so that we can use these rooms as medium-size scoring facilities. And there will be two control rooms, plus an ancillary 5.1 mixing suite. Because the building was built in 1927, we need to be very careful about earthquake safety and these kinds of considerations.

We're literally going to suspend these new floors off the construction that is going to be built on the inside of the building without disrupting any of the workings of the ground-floor studios. This is where all these little tricks that I've learned over the last 20 years are all coming together.

Have you done anything like this before?

Not of this scale. It is actually a multi story building. The rooms are so famous that you can't screw around with them. I've been able to work with Village for almost 15 years now; there is something very personal about that studio. I believe in leaving a legacy by building these entirely new rooms in that specific location. In terms of how we are gonna do it [effectively jack up the entire upper floors, and suspend the new rooms on isolated pillars driven into new foundations], we've identified 10 possible locations and that's going to be the maximum. And we will have wide-flange beams attached to structural steel columns; they'll probably measure about 20 by 24 inches or so. The columns will go up three stories to re-support the roof. I'm creating another support system on the other side of the roof so as to be able to literally suspend the entire isolated floor 16 feet in the air.

You are also involved with Lobo Recording, on Long Island. Another Scoring Stage?

There are few large studios in the Greater New York vicinity where you can record an orchestra. Lobo's owners came up with a fabulous idea of building a professional-grade scoring facility near Great Neck, Long Island. They're very close to all the mansions; Sting has a house there; Billy Joel; all of those people. Rather than going into Manhattan, they can stay out in Long Island and bring the orchestra to them. We're doing three rooms, one of which is a large stage-type space in the basement. There are already two minor recording facilities on the second floor. The first studio will probably be in operation during May. The very first project lined up is an album with Les Paul and friends on his 82nd birthday. I hope that we can find John Sebastian and Keith Richards and these people; Bill Wyman, Bonnie Raitt and all his old buddies to play along with Les. It's gonna be a wonderful project - Les hasn't recorded anything for such a long time.

You are also building project studios for Glenn Frey and Don Henley here in LA. What's the angle?

It's completely coincidental that I should be working with both of them. Henley was referred by Robbie Jacobs, an engineer who worked at A&M Studios. Don had asked me years ago to look at buildings in the Santa Monica area, and Malibu. Finally, I got a call about a year ago, saying "I've got this house in Malibu. Can you come over and build me a studio in it?" We have been working on that a good six months. It's no great hurry. Meantime, Don is doing sessions in various studios here in Los Angeles [including Record Plant, Hollywood], and he's very involved with the Walden Project in Boston.

At the same time, Glenn decided to move his studio from Aspen, Colorado, back to Los Angeles. I got in touch with Glenn through Elliott Scheiner, who I happened to be chatting with at Conway Recording while Elliot was mixing some live Fleetwood Mac tracks. He very kindly congratulated me on the efficiency of Conway, and how he liked to work there. A couple of weeks later I got a telephone call from Glenn Frey, saying: "I just spoke with my man Elliot; you're on." I had lunch with Glenn, and I immediately got a good sense of what he was about.

What was Glenn looking for? A place to hang out and cut tracks?

Exactly. It is in a very anonymous looking old building in West L.A.; a medium-size room, sort of the size of Studio "D" at Village Recorder. We're going to use a lot of wood and natural materials - a "Lumber Look." You can just imagine Glenn in Timberland boots and a plaid shirt, right? Nothing fake about him!

Tell me about the new Bouquet Digital Studios film/video complex in Port Hueneme, California.

I was asked to handle the acoustic sound isolation for the facility because the existing plant is right across Pacific Coast Highway from a National Guard airport runway. They only use it for touch and go and maneuvers by fighter jets, but there are these huge C41 air freighters that will actually fly over maybe 300-400 feet up. It became a matter of taking on the entire job, not just doing the layout and acoustics. It is going to be another two years before it's complete.

Another project in New York intrigues me. 99 Attorney Street Studios was formerly a silent movie theater. It's been vacant that long?

Yes. This silent movie theater has been sitting empty for about 40 years, and was being used for Tupperware parties; you name it. A friend of mine, Tom Nastasi happened upon it and signed a lease. It's still got the original organ from the silent movie theater - Tom's keeping it, of course. It's got a fly tower because, before it was a silent theater, they used it for burlesque shows. So there is actually a stage with a hall down below, and about a 35-foot fly space. We're building the control room where the stage used to be, and then tiered back so that it's looking into the theater, which is going to be the recording space. It's well over 100 feet deep and 50 feet wide, with a 27-foot high ceiling. It's on Attorney Street, on the lower East Side of Manhattan.

| Woodstock Studio, Karuizawa Japan built 1992

Photo A.Ishikawa |

Let's look at Burnish Stone Studio, at Setagaya, Tokyo, where you designed three studios over a period of four years in the early Nineties. The basement, first and second floor of an apartment building have been outfitted with isolation and interior acoustical treatment.

My first contact was through [producer-engineer] Joe Chiccarelli, who had been working a lot in Japan with various Japanese artists. He introduced me to a man they call Jinyama, a music producer and coordinator of bands in Japan, who in turn introduced me again to various clients. The first one was Burnish Stone Studio; the most recent is One Voice Studio. Woodstock Studios was also part of that exposure to Japanese clients. That facility was a challenge because it w as more than a just a studio; more an environment. It has a very Japanese form - a certain austerity, with floating tapered beams across the larger common areas. We liked the idea of being able to see from pretty much every space the local volcano peak, which is towering over the location. Oddly enough, on one occasion I had just visited Bearsville Studio in upstate New York, which is close to the town of Woodstock. I said to my Japanese client - while standing there on the volcanic slosh and melting snow - that it reminded me of Woodstock. They liked idea so much that they called the studio "Woodstock." Originally, it was called The Karuizawa Project, because if you say "Woodstock Studio" everyone always thinks that it's in upstate New York. However, in Japan, everyone knows it as "Wood-Stock-Ku."

| Sony Music Studio "D" Manhattan built 1995

Photo: D.Einer |

I see that Woodstock was completed by GETT Architects, Waterland and Nippon Sheet Glass Amenity. What is a glass company doing building studios?

They actually were part of the contracting team. Nippon Sheet Glass is very well known in Japan as an acoustical contractor. In Japan there is a great emphasis on privacy. As a glazing company, the Japanese mind connects glass with non-privacy, and therefore it has to have a privacy amenity. That's quite literally what the company is called. And they also provide sound isolation. Japan is such a tightly packed country, with offices next to highways and trucks running past day and night, that sound isolation through double- and triple-glazing is very important.

What are the basic rules for building a studio?

For a control room, it's entirely geometry, geometry, geometry! For a studio area, there is a lot more freedom to play around with shapes and materials. For the performance space, lighting and circulation are very important, so that there is never a sense of stuffiness. I tend to get selected as a designer because I like to build a room for orchestral performance. Which, in a sense, comes from my initial interest in theatrical design and auditorium spaces.

Control rooms are designed by geometry. If you start from the stereo approach, and admit that there is a left side and a right side, there is a symmetry to the room. You need to maintain that symmetrical sound field between left and right. Then left and right can be assumed, mathematically, to be identical. There are two other factors in a control room. Is the before-reflection and after-reflection sound field direct or diffuse, and will it be from the front of the room or the rear of the room? So there are essentially three elements [to be considered] every time we design a control room. The left/ right symmetry; the front/back balance; and also the left-top and -bottom or right-top and -bottom intersecting areas. If we take a cube and you slice it perfectly in half three times, you end up with eight little cubes. Those eight cubes have to be intersecting and balanced with one other, depending on where you choose the intersection of the slices. That's my job. I see a lot of rooms that get the gist of what is a van Haaff or Waterland knockoffs, in appearance, but they don't take care of the geometry and those important relationships.

What about the acoustic design for surround sound and DVD remastering? Maybe spotlight the new 5.1-channel Studio "C" at A&M Studios?

5.1 is more than just a buzz word. There is a fantastic market for archival materials being re-remastered to DVD-Audio, in a way that has more emotional impact. Bob Margouleff has been working a lot with DTS people, and Elliot Scheiner is working on Eagles remixes. DVD is an exciting medium. A&M had the opportunity to put together a specialized, 5.1-channel room with a Euphonix [CS3000] board, which is ideal for them. [A&M's recently remodeled Studio C is intended for multi-channel mixing, DVD pre-mastering, mix-to-picture and related sessions.] It was quite a challenge, given the narrow space we had available. I tried to maintain the sense of it being able to reach everything from the console - a bit like being in a yacht galley - so the engineer doesn't have to walk anywhere. Maybe it's a lazy man's dream!

What advice would you offer to owners of smaller project studios? How can a room or garage be turned into a recording or mixing area?

Don't overdo it with room design and acoustics. Concentrate primarily on making yourself comfortable and create a good space for your precious equipment. That includes good lighting. It includes a certain amount of sound isolation so as to not to bother the neighbors, or for that matter the [domestic partner]. Don't wake up the kids!

There's a very pragmatic approach: Tack up a piece of sound board in the place where you don't like the reflection from a wall. And don't go and buy $500 manufactured pieces of equipment to counteract the reflection. Sound board is available at Home Depot for $5 a sheet. There it is; it's done. You can use Sonex and other acoustic foams if you really want to spend lots of money. There really isn't much more difference; it maybe looks more professional - some people get off on that. If you want bang for the buck, go look around your local hardware store. We really don't need highly-paid acoustical engineers to tell us to adhere to precepts that are pretty intuitive. Symmetry is a good plan. If [the space] is not symmetrical, but comfortable, let the comfort override the dogmas. Don't expect it to get outrageously loud. Anyone can give me a call. (Laughs). Such a deal! I do design by fax, or I call it the "Napkin Treatment."

Tell me more about this "Waterland Frontwall," which is currently in use at Brickhouse Studios and Sublime Studios. Basically, it's a transportable monitor wall built by a firm called Total Fabrications, under the direction of Ian Coles. How did it come about?

Total Fabrications used its expertise in constructing stage trusses to develop a system that could be constructed off-site and the assembled in a around 10 hours at a client's studio. Waterland makes the Frontwall available for sale, or on a per-project basis. Our mechanics unload, genie lift, guy and bolt the trusses together; it can be removed just as easily. Frontwall ensures that you will have a rigid sound source, and that the first sound reflection will be solid. It must still be placed within the existing reflective fields of the room since the source vibration needs a volume of air within which to develop. The space itself may also need to be treated acoustically.

It's made of strand-board foam sandwich custom panels that are camlocked to the rigid frame. All the active and reflective acoustic surfaces are positioned in a proven geometric relationship within the room. Outstretched wings are guy wired to the rafters to provide maximize mobility. We think that Frontwall is the smart way to go in many situations. Not only does it broaden the owner's choices as regards to leasing or buying the building, it also shortens the time required for construction. It also provides a precise acoustic form that otherwise only specialized construction teams could provide. and, since it can be leased from Waterland, the design broadens the client's budgetary options. We've actually sold three of them during the last two years. It's an intermediate between a recording studio and a live setup. They cost around $60,000; we rent them for around $2,500 per week, which is 20% of the cost of actually renting a recording studio. We installed one at Bryant St. Studio, San Francisco, in 1994.

What other studio designs do you admire?

I think Starstruck in Nashville is a fabulous example of what Neal Grant and his wife can do; I think he did a fantastic job.

What about studio designers that also offer equipment packages? I was thinking of studio bau:ton and its recently formed tec:ton division.

I think it's a complete conflict of interest to sell equipment and design the environment at the same time. It is not justifiable, because tec:ton is obviously going to earn some money from the sale of equipment. If I have to be a judge of the quality of a project, I want to have as little as possible to do with the guarantees on the equipment. I cannot compromise.

Interestingly, Peter Maurer [partner with Peter Grueneisen in studio bau:ton] and George Newburn [one of the partners in Studio 440] originally worked for Waterland. Just as I decided that I could stand on my own two feet and didn't have to work for Sierra Audio anymore, their moment came [to part company]. I think its wonderful to actually leave a trail. But my philosophy is to proceed carefully; I'd rather go slow than hurry and not maintain the quality. My adage has always been: "To hurry takes too much time." If you rush into a project and you're over-enthusiastic, it might fizzle out or bite you in the ass!

If you could be reborn as anyone, who would that be?

Magellan! He did some amazing things. I think Marco Polo, Magellan and those [early explorers] were very daring. The earth shaking changes they brought about - from bringing us cayenne pepper, to unlocking a whole continent.

All photography courtesy of and ©2001 of Waterland Group.

©2025 Media&Marketing. All Rights Reserved. Last revised:

01.04.25

|

Vincent Van Haaff, president of LA-based Waterland Group, is a renaissance man who puts the quality of his designs above all other criteria. As he readily confesses, his studio designs are based on equal amounts of aesthetics and acoustical science, with a focus on the specific tastes and personality of the facility's owners. For van Haaff, a recording studio or post facility is more than just a space in which we record or mix a project. "It is," he concedes, "a carefully crafted environment in which we witness the creation of sonic art."

Vincent Van Haaff, president of LA-based Waterland Group, is a renaissance man who puts the quality of his designs above all other criteria. As he readily confesses, his studio designs are based on equal amounts of aesthetics and acoustical science, with a focus on the specific tastes and personality of the facility's owners. For van Haaff, a recording studio or post facility is more than just a space in which we record or mix a project. "It is," he concedes, "a carefully crafted environment in which we witness the creation of sonic art."